Breaking down mental health stigma

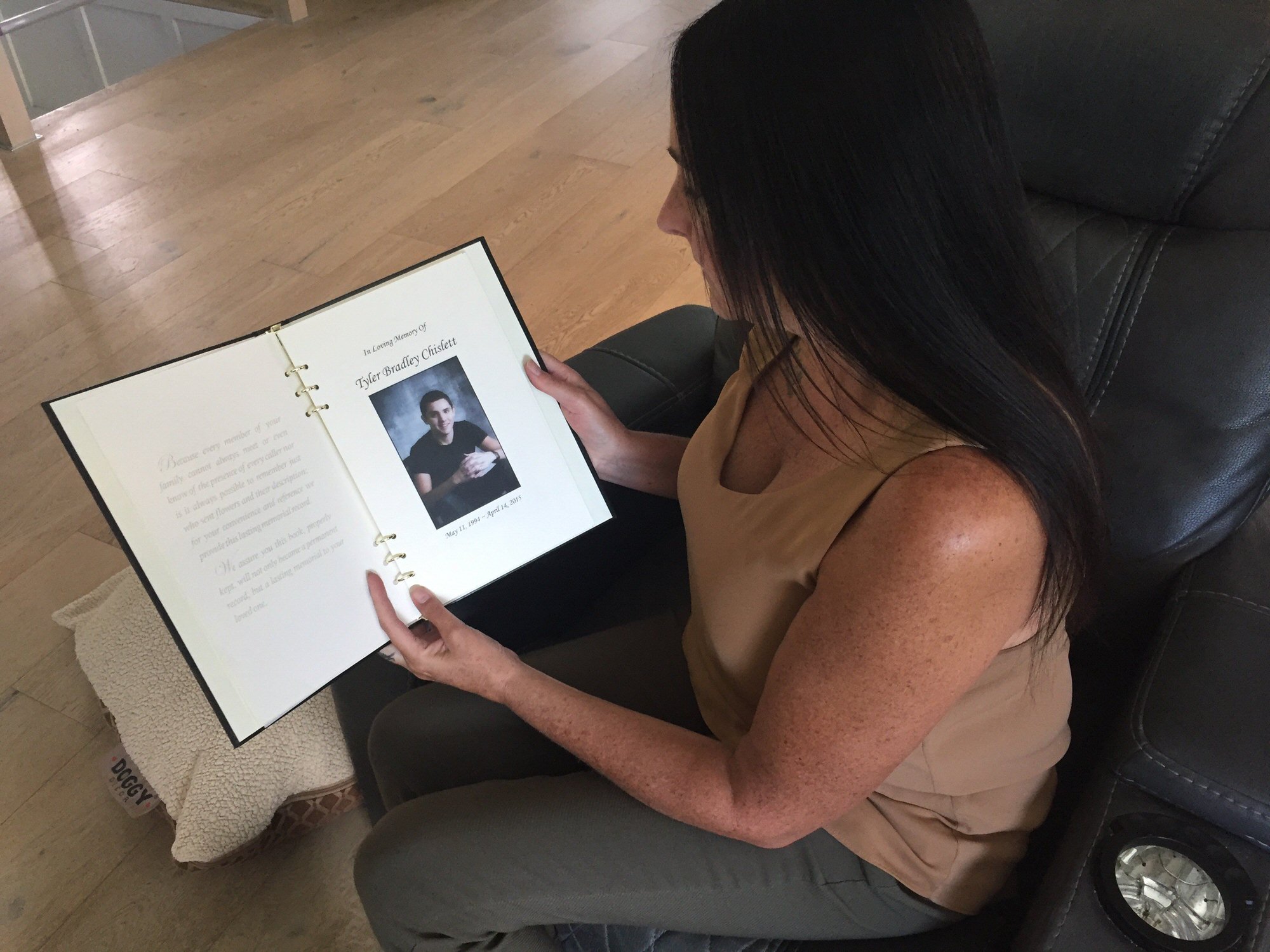

Ann Chislett became a mental health advocate after she lost her son to suicide

September 10, 2020

By Lisa Brunelle, Communications Advisor, Covenant Health

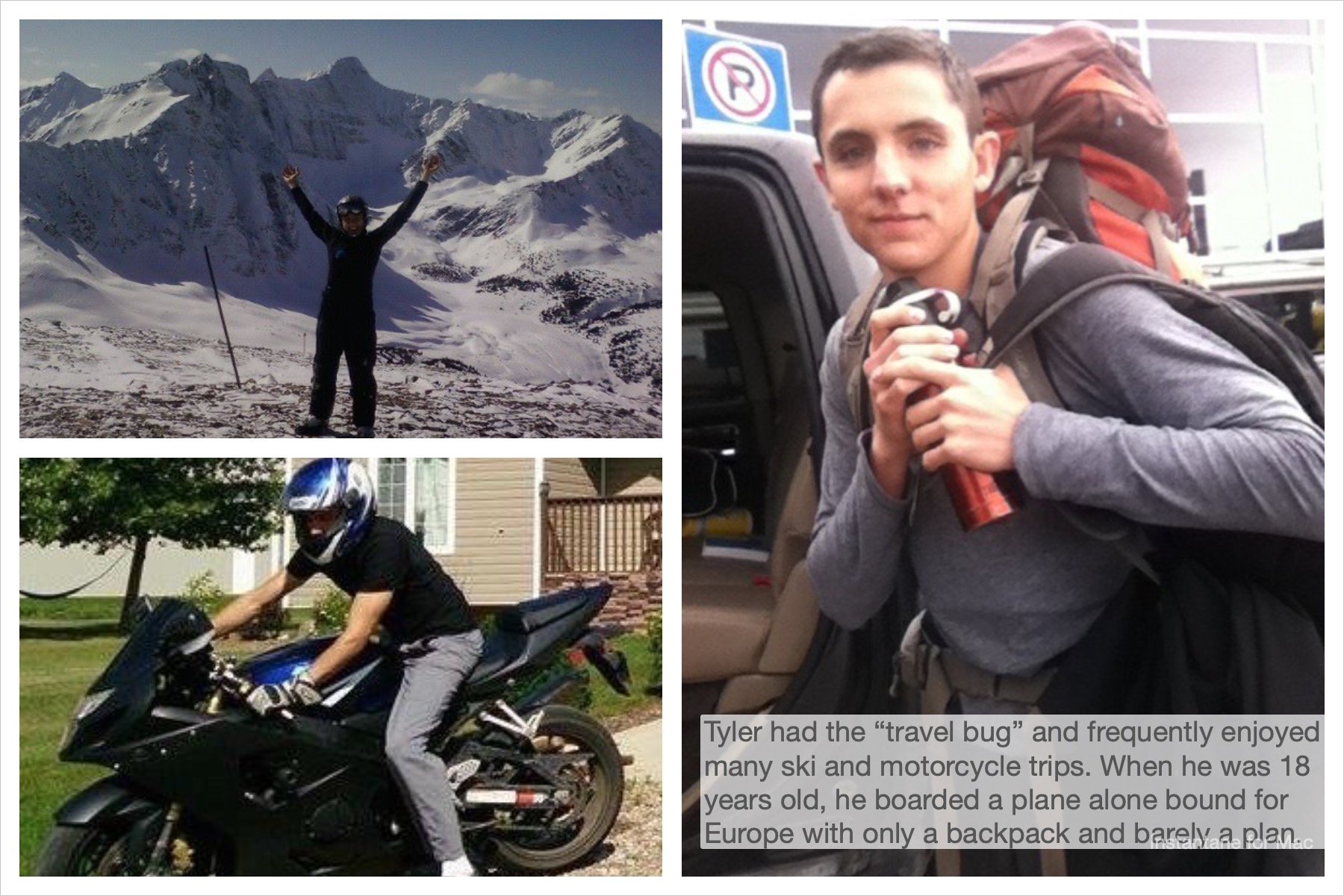

If someone had told Ann Chislett when her son, Tyler, was 15 that he would be dead in five years, she wouldn’t have believed them. He was an active, adventurous teen who was full of life.

“Not only did he pass away at the age of 20, but he suffered for years and took his own life,” says Ann Chislett, an administrative assistant at the Bonnyville Health Centre. “At the time, I didn’t understand mental illness. I didn’t understand that it’s not a choice you make or something you get over.”

Since Tyler's death by suicide, Ann has become a mental health advocate because she wants to find ways to help families and individuals who are struggling with mental illness and to support access to resources.

Tyler's death prompted the creation of the Tyler Chislett Memorial Fund in 2016, in memory of his life lived and with the aim of helping others. Run by the Bonnyville Health Foundation, the fund supports mental health education for healthcare workers so they can better support those in their care and themselves. Ann plays a key role in the activities the fund supports.

The Canadian government reports that an average of more than 10 Canadians die by suicide in Canada every day. Men and boys are at higher risk for suicide than females. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for 15- to 24-year-olds.

Before Tyler’s death, Ann and her husband, Tim, were like many others in their worry about the stigma that surrounds mental health issues. When they were trying to find ways to help Tyler, they didn’t want people to know what their family was experiencing, and there were limited resources available to support them.

“I think stigma is one of the biggest barriers to people getting help for mental health,” says Ann. “We felt very alone in our pain as parents. Tyler was an adult, so we were excluded from his treatment and weren’t given any tools to support him. As far as we know, there was never a final diagnosis as to what mental health issue he was dealing with.”

Ann says she and her husband desperately sought answers, spending hours on the Internet, reading books and praying for help.

“Tyler was our only child. He was a compassionate person, with a gentle, introspective demeanor that was evident from a young age,” says Ann. “He was very generous and passionate about anything he did.”

Tyler loved to ski; he embraced downhill slalom and was a giant slalom racer. He travelled often with his family and participated in mission trips to Ecuador, where he helped build schools. He also served as a volunteer on the long-term care unit at Bonnyville Health Centre.

After graduating from high school, Tyler moved to another city to study political science and law. He was at university when he died by suicide. Before his death, he participated in several programs in hospital settings, looking for mental health support.

Looking back, Ann realizes that Tyler was showing some signs of mental health challenges before he turned 18. It wasn’t until he became an adult that she and Tim realized how much he was struggling and that he couldn’t seem to find help. He stopped eating, isolated himself and stopped doing the things he loved. His friends noticed but didn’t know what to do to support him.

“I’ll never forget the day Tyler died,” says Ann. “It was 5:15 p.m. on April 14, 2015, and I was on the phone with my mom when my brother called me on another phone. When I got on the phone, I knew immediately Tyler was gone because he had made it really clear he felt no hope. He had attempted suicide before, and he did not receive the help he required. His mind and body were tired and couldn’t fight anymore. Tyler didn’t choose to die. He just didn’t know how to stay any longer.”

After Tyler’s death, Ann became an advocate for mental health. Her family’s experiences and struggles convinced her that people, including those on the front line, need more resources.

“The last two years of Tyler’s life forced us to open our eyes to mental health,” says Ann. “In my opinion, it’s just as insidious as any cancer.”

Tyler felt rejected by many due to his mental health struggles, says Ann. She was devastated to see him change.

“It was one thing to watch Tyler go from a thriving, adventurous, beautiful human to a person who loathed himself and felt socially rejected due to his illness,” says Ann.

And sometimes the stigma came from unexpected places. Ann shares a memory of a time when Tyler was being treated for mental health in a hospital. He was feeling pretty good, and the two were having coffee in the cafeteria. Beside them was a table of hospital staff, and they heard one of the staff members say, “I hate going onto the psych unit. I get the shivers every time.” Another person at the table said, “Try working in the emergency department. We’re always dealing with those people.” They all laughed, and Tyler cried, says Ann.

Mental health activities in Bonnyville

Soon after Tyler’s death, Ann began advocating for mental health, and she found support. The Bonnyville Health Centre established a mental health steering committee to identify gaps in the community. The group included the school boards, municipal district and local Indigenous groups.

At its gala in 2016, the Bonnyville Health Foundation launched the Tyler Chislett Memorial Fund, which supports mental health education for healthcare workers. At that gala, Ann and Tim donated $1,500 to the fund, and the auctioneer invited everyone in the room to come up and donate $500. Within minutes, $40,000 was raised. To date, over $70,000 has been raised at the annual galas and other fundraising events.

“Tyler would hate that the fund is named after him,” says Ann with a smile. “I like it because using his name on it makes it more personal and more real to people.”

The fund helps recognize important days like Bell Let’s Talk Day, World Suicide Prevention Day and World Mental Health Day.

“The fund gives Tim and me hope that things will get better,” says Ann. “Every donation people make proves we need to advocate for more resources. It’s also a reminder that people in rural Alberta won’t be forgotten. We’re going to fight for our kids!”

And we can all help, believes Ann.

“We need to do better as humans to care for everyone without judgment,” says Ann.

If you or someone you know needs help, there are resources available 24/7. Call the Mental Health Help Line at 1.877.303.2642, call Health Link at 811 or call 211 Alberta.